Starship Flight 7 - What to expect

SpaceX is targeting no earlier than January 13th at 4 pm CDT for the 7th launch of their Starship launch vehicle! While releasing the official date, they’ve released a bunch of incredible information on the flight. If you think you know what they’ll be doing on Flight 7, trust me, there’s more. From the first payload deployment to an engine relight in space, from the first test of an actively cooled heat shield tile to a possible catch-like simulation, you don’t want to miss this flight.

Flight 7 vehicles

Starship is a 2-stage launch vehicle, composed of the Super Heavy Booster and the Starship second stage. The first one is about 71 meters high, and it is designed to return to the launch site after stage separation and be caught with the chopsticks on the same tower it launched from (like it did on the historic Flight 5). Starship is the upper stage, designed to go to space and carry the biggest payloads ever; like the first stage, it’s designed to be reusable and be caught by the chopsticks as well. While on previous flights, Starship was 50 meters high it is now 51.8 meters high, because it’s in the Block 2 configuration, which we’ll talk about as we explain these amazing vehicles!

Booster 14

Booster 14 during its static fire. Credit: SpaceX

Booster 14 is the Booster used for this flight, and it features several changes compared to the previous Boosters: the most prominent changes are reinforcements in several weak places, most notably on the chines, and a new set of stringers to radially reinforce the area below the cowbell vents. Additionally, only 32 of the 33 Raptor engines will fly for the first time, as SpaceX plans to reuse a Raptor engine from Booster 12 to verify reusability capabilities and performance; while SpaceX has not confirmed what engine will be reflown, it’s likely R314, the “pi” engine, which is one of the 20 outer engines, or at least was on Booster 12; reusing one of the outer engines is smart, as it wouldn’t be wise to risk one of the 13 inner engines, needed for the catch. Booster 14 also features key upgrades to its software and catch criteria, a direct consequence of Booster 13’s upgrades; since it will attempt a landing on the chopsticks, the tower has also been upgraded, both hardware and software: with the radar sensors, communications tower, and chopsticks reinforced, and the software updated, SpaceX aims for a flawless catch this time, but only if the criteria are met.

February 9th, 2024: Booster 14 aft tank #2 is spotted.

February 15th, 2024: Booster 14 stacking begins in Megabay 1, after B14 A2:4 and B14 CX:4 rolled inside in the past few days.

April 26th, 2024: Booster 14 stacking is completed in only 71 days, beating the previous record (Booster 13, 151 days) by more than half.

October 3rd, 2024: Booster 14 is rolled to Massey’s for its cryogenic test campaign.

October 4th, 2024: Cryo test 1 of Booster 14’s CH4 tank.

October 5th, 2024: Cryo test 2 of both tanks of Booster 14.

October 7th, 2024: Booster 14 is rolled back to the Production Site.

December 5th, 2024: Booster 14 is rolled to the Launch Site.

December 7th, 2024: Spin Prime: maybe SpaceX decided to verify everything was working after skipping it on Booster 13, or maybe it’s related to the installation of R314.

December 9th, 2024: Static fire: successful static fire of all 33 Raptor engines, with a burn that lasted 9 seconds.

December 10th, 2024: Booster 14 is rolled back to the Production Site.

December 30th, 2024: Booster 14 is rolled back to the Launch Site for launch.

January 9th, 2025: Ship 33 is stacked atop Booster 14.

January 10th, 2025: The Flight 7 full stack conducts a Wet Dress Rehearsal.

Ship 33 - The first Block 2 Ship

Flight 7 will be a historic flight, as it will feature the first Block 2 Ship, which is the new generation of Starship. As a reminder, the Booster will still be Block 1, but a Block 2 version is also scheduled (as of writing, Boosters as far as Booster 17 are still Block 1s). Being a new-generation ship, explaining the detailed changes is not as simple as the past flights, as there’s a complete redesign, so if you want a recap of the major changes, keep reading, but if you have time (a lot of time), we recommend reading the dedicated and extremely detailed articles of Ringwatchers.

Ship 33 on its way to Massey’s. Credit: SpaceX

Dimensions: Block 2 has changed in height, gaining 1.8 meters thanks to the addition of a stainless steel ring, making the new-generation ship equipped with 21 rings plus the nose cone.

Forward flaps: the most notable change is that the forward flaps have been completely redesigned, and they feature a lot of changes: they’re smaller, and they’re spaced 140° apart instead of 180°; they’re located lower on the Ship and closer to its “belly,” the leeward side, so that they should be completely shielded from the heat of reentry, eliminating the hinge burns that occurred for the past 3 flights. Their new design is also better for the aerodynamic descent, as the aft flaps don’t have to compensate for the tendency of raising the nose cone anymore.

Extended tanks and new header tanks: a thing you’ll certainly notice during propellant loading, the Ship’s tanks have been optimized and lengthened, giving enough volume for 300 tons, or 25%, more fuel, for a total of 1500 t. This will allow Starship to carry heavier payloads, up to 100t (per SpaceX); the header tanks (which are secondary tanks used for every burn after SECO) have been redesigned to avoid propellant sloshing and fluid problems, especially for future long-duration missions. The internal plumbing, including the fuel transfer tubes, has also been redesigned.

New heatshield: the heatshield is now composed of approximately 18.500 tiles, which have been optimized in some areas, but the key feature is the ablative layer underneath, to protect the Ship’s body in case one of the tiles breaks or falls off. This launch will also feature many interesting experiments, featured in the explanation below.

Payload bay: the volume that has gone to the tanks has been taken off from the payload bay, which has gone from a 5-ring to a 3-ring section; however, thanks to optimizations of the hardware inside of the nosecone, more space is now available for the payload.

Propulsion: Ship 33 still features Raptor 2s, as many of the upcoming Ships will for quite some time, until Raptor 3 becomes operational; however, SpaceX has optimized the propulsion of the Ship, has vacuum-jacketed the feedlines, have designed a new, more efficient downcomer for the RVacs, and improved valves and sensors.

Avionics: there has been a complete redesign of the avionics, which include upgrades to the flight computer, more antennas including Starlink, GNSS, and RF communication systems as backups, new sensors for navigation and tracking, new smart batteries and power units than distribute over 2.7 MW of power across 24 high-voltage actuators, and more than 30 cameras to give beautiful and important views on the ground.“Additionally, SpaceX has confirmed the ability to stream 120 Mbps of data throughout the flight.

January 6th, 2024: Ship 33 nosecone is spotted in Starfactory; however, it will be moved to Megabay 2 for stacking on July 14th, 2024.

July 14th, 2024: stacking of Ship 33 begins.

August 23rd, 2024: stacking of Ship 33 is completed in only 40 days.

October 26th, 2024: Ship 33 is rolled to Massey’s for cryo testing.

October 28th, 2024: Ambient pressure test

October 29th, 2024: Cryo test 1, a partial cryo of both tanks.

October 30th, 2024: Cryo test 2, a full cryo of both tanks.

October 31st, 2024: Cryo test 3, a full cryo of both tanks.

November 1st, 2024: Ship 33 is rolled back to the Production Site for engine installation.

December 11th, 2024: Ship 33 is rolled at Massey’s for its engine test campaign.

December 12th, 2024: Spin prime: given all the internal changes, it’s no surprise SpaceX has decided to go on the safe side and conduct this test.

December 15th, 2024: Static fire 1: for the first time, a Block 2 Ship ignites its engines, all 6, for about 6 seconds.

December 16th, 2024: Static fire 2: Ship 33 ignites its single Raptor engine for a few seconds to practice an in-space relight.

December 17th, 2024: Ship 33 is rolled back to the Production Site.

January 7th, 2025: Ship 33 is outfitted with its 10 Starlink simulators.

January 9th, 2025: Ship 33 is stacked atop Booster 14.

January 10th, 2025: The Flight 7 full stack conducts a Wet Dress Rehearsal.

Flight profile of Flight 7

Flight 7 of Starship will possibly be the most amazing so far, with a lot of changes and tests, so let’s dive right in: we’ll start with the pre-launch activities, where some changes to propellant load timelines have been implemented compared to Flight 6: after the GO/NO-GO poll conducted by the Flight Director at T-1h15m, propellant loading will begin, starting at T-44m59s for the Ship LOX load, followed by the Ship CH4 load starting at T-42m20s; these are 4m51s and 6m59s earlier than the previous flight, respectively, which means the ground systems have been updated. Booster loading instead has remained pretty much the same, with the CH4 loading starting first at T-41m24s, just 9 seconds earlier, and the LOX loading starting at T-35m28s, which is 11 seconds later. In the middle of the propellant loading activities, at T-19m40s, both the Booster’s and Ship’s Raptor engines will begin the engine chill procedure, where a small amount of cryogenic propellant is run through the turbopumps to avoid thermal shock at ignition… like the past flights since Flight 2, this has not changed. Finally, at T-3m20s and T-2m50s, the Ship and Booster will respectively wrap up their loading, and at that point the final part of the countdown will occur, featuring the GO/NO-GO poll for launch at T-30s, followed by the activation of the Water Deluge System (for sound suppression and damage reduction) at T-10s, and then, finally, Raptor ignition at T-3s.

When the Raptors ignite, there will be a tiny period of time where Starship builds up its thrust before lifting off at T+2s! During the ascent, Starship will experience Max-Q, or the moment of peak aerodynamic stress on the rocket, at T+1m2s, leaving the characteristic plume; at T+2m32s, Booster 14 will cut off 30 out of its 33 Raptor engines (a maneuver called Most Engines Cut Off, or MECO), and 8 seconds later Ship 33 will light its engines in flight for the first time in Block 2 history, pushing away from the Booster in the so-called hot staging maneuver. Just 6 seconds after separation, the Booster will light its inner ring of 10 Raptor engines, in addition to the central 3, and begin the boostback burn to come back and be caught; interestingly, with the cutoff of the boostback burn at T+3m29s, the burn will only last about 43 seconds, much less than the roughly 54 seconds it lasted before; this is likely due to the Ship’s extended tanks, which allow for an earlier cutoff of the Booster, and an earlier separation. If the Flight Director sends the command for the Booster to come back, then it will aim for the catch tower and attempt a catch, but if the command is not sent, then it will automatically abort to the Gulf of Mexico, roughly 30 km offshore. Hopefully, we’ll hear a nice “GO for catch,” and we’ll see a jettison of the hot stage ring (2 seconds after the end of the boostback burn), followed by a catch, like Booster 12, but with less damage, faster, and less flamy.

The landing burn is supposed to start at T+6m35s and end at T+6m55s, lasting slightly less than Flight 5’s and Flight 6’s landing burns. After the Booster’s landing burn, whether on the catch tower or offshore, the Ship will cut off its engines at T+8m53s, concluding a 6m13s long burn, the longest for a Ship to date. After the cutoff, Starship will have entered its suborbital trajectory, taking it on course for a splashdown in the Indian Ocean, but first comes the coast phase: in the past 3 flights, except for a Raptor relight on Ship 31, the coast phase had been relatively quiet until reentry, but not this time, because at T+17m33s, the payload deploy demo will begin, deploying 10 dummy V3 Starlinks, marking the first payload deployed by Starship! It’s unclear how much this will last, and how much time the payload bay door will remain open, but it’ll be interesting to see for sure; then, at T+37m33s, Ship 33 will attempt a relight of a single Raptor engine, proving the capabilities of the new header tank design; the burn is expected to last a few seconds, probably not more than 5 seconds, based on SpaceX’s test.

Less than 10 minutes later, at T+47m14s, Starship will begin its reentry phase, where several experiments will be tested out: first of all, entire sections of the heatshield have been taken off from the sides, pushing Starship to its limits once again; then, it looks like some tiles have been taken off the heatshield in various locations, while several are made of different metals, including one featuring active cooling (where the Ship’s cryogenic propellants are used as a cooling method). Ship 33 will also have some non-structural catch pins integrated, testing their resistance to the heat of reentry, for a possible catch as soon as Flight 8; additionally, the entire heatshield, which is new, will be tested out. If Ship 33 survives reentry, we shouldn’t see the burn throughs on the forward flaps’ hinges anymore, and we’ll see those tested out as well during descent. As Starship nears the surface of the Indian Ocean with a greater angle of attack, 1h6m13s after liftoff, at less than 1 km of height, it will conduct the landing flip, followed 6 seconds later by the ignition of the 3 central Raptor engines for the 20s-long landing burn, culminating in a soft, on-target splashdown in the Indian Ocean. This is possibly the last suborbital flight of Starship (excluding point-to-point), as SpaceX intends to attempt a catch on Flight 8 and therefore go orbital. It will be a flight packed with tests, simulations, and a lot of data gathered, useful for making Starship a fully reusable rocket, ready to propel humanity into the stars.

Flight 7 full stack during its Wet Dress Rehearsal. Credit: SpaceX

Possible catch-like simulation?

Note: the following part is based on speculation and interpretation of events, and it does not rely on any official source.

As Elon Musk said on X after Flight 6, SpaceX may be attempting to catch a Ship as soon as Flight 8, which is only the flight following this one. If Ship 33 survives reentry and descent, validating the heatshield and forward flaps design and the landing, validating on-target accuracy and header tank design, then there’s a real possibility that they might be attempting the catch next flight. But, like with the Booster, there will need to be preparations.

That’s why we’ve formulated the hypothesis that SpaceX might conduct a catch-like simulation with the chopsticks while the Ship lands during Flight 7, and here’s why:

On December 30th, just before Booster 14 rolled out to the launch site, the chopsticks conducted a series of catch-like tests, as usual before a flight or a lift. After rising to the top of the tower, they closed slightly at 1:16 pm CDT and then reopened. They stayed in that open position until 2:13 pm, when they both slightly closed again; finally, at 2:20 pm, they closed in a catch-like mode and began descending to the base of the tower, following the completion of the tests. But you might notice how the gap between when they first closed slightly and when they closed in a catch-like mode is 1 hour and 4 minutes, exactly the time between liftoff (after which the chopsticks slightly close to begin automated health checks) and the Ship landing in the Indian Ocean.

The full catch-like tests of the chopsticks. Credit: NASASpaceflight and StarbasePulse on X.

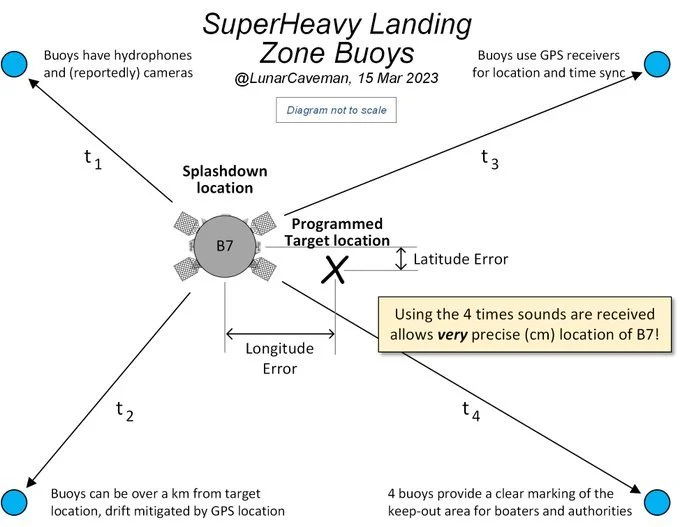

But that’s not all: in the Flight 7 news release of SpaceX, they specified they will be testing radar sensors on the chopsticks “with the goal of increasing the accuracy when measuring distances between the chopsticks and a returning vehicle”; while this applies to the Booster, it most likely applies to the Ship as well. Going back to Booster 11’s water landing, you might remember that SpaceX used 4 hydrophone-dotated buoys, placed at the angles of an imaginary square, and they measured the time that the sound took to reach them, determining the Booster’s accuracy to a cm-level precision; at the same time, the tower made a catch-like simulation. Additionally, Gav Cornwell has spotted 4 buoys at Port Canaveral that were used for Flights 5 and 6 and, possibly, Flight 4; the accuracy determination method might be the same to determine the Ship’s accuracy during splashdown.

The plan for the accuracy determination during a Booster’s landing. Credit: LunarCaveman

So the only thing SpaceX has to do is a catch-like simulation at the same time as Ship 33 lands, and the evidence said above shows that this might indeed be in the cards. But you might think: what about the Booster? Won’t it be between the chopsticks? We believe that SpaceX’s “faster safing procedures” might allow Booster 14 to safe itself quickly enough and be put on the OLM, while the chopsticks do the simulation.

Why? Due to orbital inclination and the Earth rotating, it’s unlikely that a Ship catch will happen 1.5-2 hours from launch, but this simulation might be to test those radar sensors on the chopsticks: possibly connected to the buoys, they might get calibrated and validate a future Ship catch, like it was done with Booster 11.

Again, this is a speculative theory, and the time of the chopsticks test might just be a coincidence, but we thought this was worth noting in case it revealed itself true.

Where and why watch it?

If you want to watch Flight 7, there are several options to choose from: you can follow SpaceX’s official stream from their website, starting 30 minutes before liftoff, or you can follow other hours-long livestreams like NASASpaceflight’s or EverydayAstronaut’s, with awesome commentary and views. If you’re thinking about seeing it live, the best advice is to go to places like South Padre Island or other places with a good view of the launch site, possibly several hours before the launch. But why watch it? Well, this is the launch of the most powerful launch vehicle ever created, the launch vehicle designed to bring humans to the Moon, Mars, and beyond! In this particular flight, there’ll be the possibility to see the amazing liftoff, the ascent, and the second-ever catch of the Super Heavy Booster, an unprecedented feat. You’ll see the debut of the new design of Starship, Block 2, and you’ll get to see Starship’s first-ever payload deployment in space! Additionally, with the ignition of a Raptor engine and a reentry full of tests, the views will be awesome! And not to mention the amazing daytime landing, which may be the last one before SpaceX decides to attempt the catch! Watching a Starship flight is an amazing experience. Whether you watch it alone, with friends, or with family; whether you watch it in real life or from a screen, excitement will be at the stars!

References

Booster 14 (B14) | Starship SpaceX Wiki

Ship 33 (S33) | Starship SpaceX Wiki

[4K] Watch SpaceX Try To Catch Starship's Super Heavy Booster!

🚀 SpaceX Launches Starship Flight 7 and Attempts Another Booster Catch